- April 13, 2022

- Posted by: pragma_admin

- Category: Uncategorized

An original piece by Pragma

Ethiopia is a country with massive unexploited renewable energy potential, from sources such as hydro power, solar, wind and biogas. However, the country utilizes a mere 7.5% of that capacity and 90% of the country’s energy demand is fulfilled through biomass such as firewood, charcoal and plant residue. As of 2020, only 44% of the total 18 million households had access to electricity, out of which 33% via on-grid electricity and 11% through off-grid power sources. This shortage is exacerbated by the increase in demand resulting from a growing population base and higher economic growth trajectory. The country’s power consumption is expected to increase by 30% annually in the coming years.

To ensure Ethiopia achieves its short-term development goals, the government introduced its ambitious National Electrification Program (NEP 2.0) in 2019, aiming to achieve universal access to power by 2025. The plan targets to address 65% of the household through on-grid facilities and the remaining 35% through the off-grid infrastructure. By 2030, the government intends to extend its on-grid access to 90% of households, through simultaneous on-grid rollouts to more dispersed communities.

The country’s national pride, GERD, that is expected to generate over 5000 MW of power, is the largest power initiative on the continent. With addition of projects such as Koysha, Ethiopia’s second largest hydro power project with a 2,160 MW potential, as well as additional select solar and geothermal projects, Ethiopia is set to generate enough electricity to fulfill national demand and export to other countries in the near future.

Off-Grid Initiatives

While the on-grid initiatives get the most public attention, the country has also been actively developing its off-grid infrastructure. The government has taken a series of important measures to establish an enabling environment, such as establishing tariff free import for solar panels with up to 15 WP and adopting quality standard to monitor such imports. Key stakeholders, ranging from energy regulators to international donor programs and private enterprises have resulted in about 1.5 million off-grid connectivity since the NEP 2.0’s conception in 2018. By 2025, the country aims to increase access to another 4.6 million households, 3 million of which will join the on-grid cohort by 2030.

Being the largest unserved market in East Africa, however, the country still has considerable runway for growth in the market. As of 2019, off-grid energy became accessible to more than 2.2 million beneficiaries. Over the next ten years, the government plans to expand off-grid energy access to around 6 million households, where many would be temporary beneficiaries until they gain infrastructure admission to on-grid connections by 2030.

Being the largest unserved market in East Africa, however, the country still has considerable runway for growth in the market. As of 2019, off-grid energy became accessible to more than 2.2 million beneficiaries. Over the next ten years, the government plans to expand off-grid energy access to around 6 million households, where many would be temporary beneficiaries until they gain infrastructure admission to on-grid connections by 2030.

Of the current off-grid beneficiaries, most of the households utilize power through standalone solar systems. A study by USAID’s Power Africa Off-grid Project (PAOP) shows that service adoption is concentrated around solar equipment with capacity less than 10 WP, enough to provide light for households. While these household-scale power systems have reduced the need for kerosene and firewood, they are still inadequate substitutes to the more energy-intensive activities such as cooking, which of an average household, and agricultural activities. Ethiopia’s implementation of its national electrification plans highlights the need to check the quality of electricity penetration – it’s not just a numbers game. Key gaps in the off-grid landscape include low mini-grid penetration in high potential areas and constrained supply of energy systems for productive use.

Mini Grids

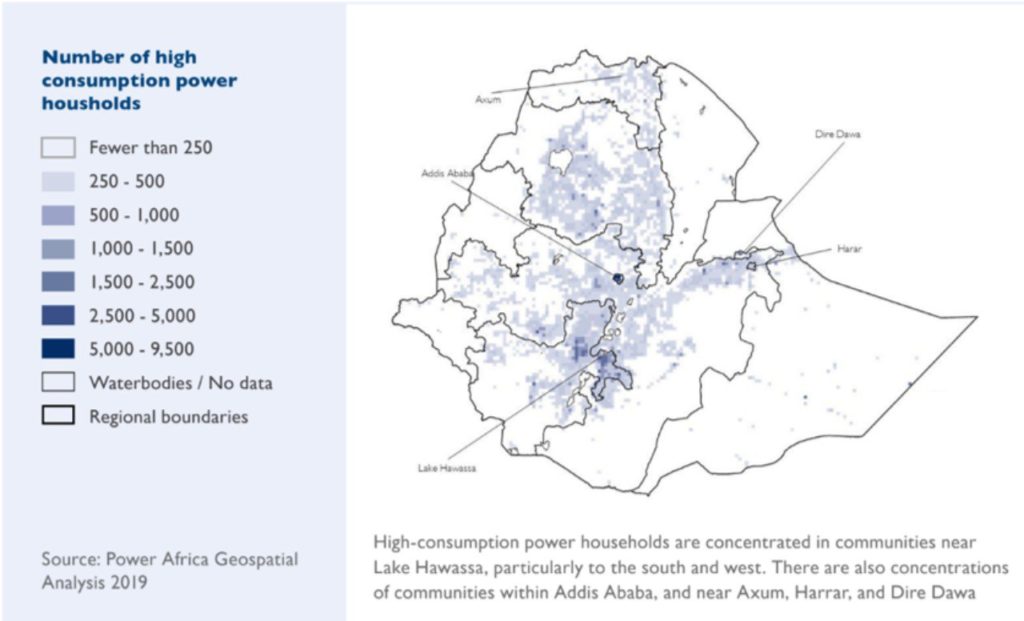

While most of the population is expected to access on-grid energy, a significant minority will require less conventional provisions. Mini grids are one such silver bullets needed to increase the country’s electrification pace. According to Power Africa’s geospatial analysis, there are over 2000 households among several clusters that lie beyond the 10 km distance from medium-voltage networks. These clusters have a relatively high average annual household discretionary spending of over $660, making them prime candidates for more concentrated energy sources that offer higher power supply per household.

Number of High Consumer Power Households Per 10 Km2

Agricultural Productive Use

Another key area that mini-grids and alternative energy systems can address is the agriculture sector, the heart of the Ethiopian economy. Ensuring more consistent power lines can significantly increase productive output of the 85% of households that rely on farming for their livelihoods. For example, irrigation is uncommon in Ethiopia, despite its estimated potential to double revenues per hectare for farms. 75% of households that depend on off-grid energy own farms. However, only 10% of them use irrigation, with 25% of those utilizing hand pumps and 13% motorized systems, further demonstrating the demand-supply mismatch. A productive application of off-grid energy lines in agriculture is to deploy solar-powered water pumping systems for town water supply, livestock watering and irrigation. In addition, energy for heating and cooling systems can aid in poultry farming, a vital but high-maintenance industry that requires multiple environmental conditioning.

Another key area that mini-grids and alternative energy systems can address is the agriculture sector, the heart of the Ethiopian economy. Ensuring more consistent power lines can significantly increase productive output of the 85% of households that rely on farming for their livelihoods. For example, irrigation is uncommon in Ethiopia, despite its estimated potential to double revenues per hectare for farms. 75% of households that depend on off-grid energy own farms. However, only 10% of them use irrigation, with 25% of those utilizing hand pumps and 13% motorized systems, further demonstrating the demand-supply mismatch. A productive application of off-grid energy lines in agriculture is to deploy solar-powered water pumping systems for town water supply, livestock watering and irrigation. In addition, energy for heating and cooling systems can aid in poultry farming, a vital but high-maintenance industry that requires multiple environmental conditioning.

Challenges

Solar irrigation pumps, mini-grids and solar cooling systems have tremendous potential to fill those market gaps, provided that the necessary regulatory and financial incentives are put in place. One of the main issues stagnating the market is lack of access to forex. With no simplified way to help customers use remittances to make purchases, a lot of the larger solar technologies remain out of reach for rural households. A related impediment is the underdeveloped financial infrastructure in the country which does not promote financing optionality for the energy sector compared to other strategic sectors of the economy that have been receiving prioritized attention.

Another challenge is the inconsistent implementation of tariff benefits. The more components a solar system has, the more likely that its different parts will be subjected to different fees. Finally, Ethiopia’s closed trade system limits foreign companies from entering the market, hampering the necessary scale and technology transfer needed to ensure the target coverage within the set timeline

A Way Forward

A leading emerging economy with an impressive renewable energy track record, and one that Ethiopia can emulate, is India. In the past there years until 2019 alone, India installed more than 180 thousand solar pumps which makes the total solar pump more than a million in the country. It had set its target for 26 million solar pumps back in 2014 and has since managed to curate various financing schemes and market structures to meet its targets. The more recent solar PV scheme, the Kusum Power Plant Scheme, was launched in 2019 to accelerate the country’s transition to its goals of increasing the share of installed capacity to electric power from non-fossil-fuels sources to 40% by 2030.

The scheme was designed to generate a total of 30.8 GW through a combination of a set of decentralized grid-connected renewable energy power plants with a 10 GW capacity, 2 million off-grid solar agriculture pumps with a capacity of 9.6 GW, and the solarization of 1.5 million grid-connected agriculture pumps generating an additional 11.2 GW of power. To quicken the electrification pace, the central and state governments will take lead on the financing, each responsible for 30% of the costs. Banks are encouraged to provide an additional 30% loan to farmers, who are expected to put down between 10% to 40% equity to get the services. Upon completion of the project, India hopes these power plants will generate sufficient electricity for household and agricultural needs – and provide a healthy surplus that farmers can monetize by selling to national power distribution companies. Furthermore, the government is expected to save USD 7.6 billion in diesel subsidy that comes from the solarization of diesel pumps.

Granted, the implementation of such a scheme has been rocky. One issue is the reluctance of lending institutions, who doubt the credit worthiness of farmers and the value of the land held as collateral and fear the opportunity cost of investing in less environmentally friendly, but more certain ventures such as coal projects. Another is the dangerously unsustainable extraction of ground water for irrigation purposes, increasing the number of “dark zones” or India’s endangered water sources the longer the problem is left unattended.

A solar-powered water pumping system in action (PM-Kusum Project, India).

In addition, energy for cooking, heating and cooling are important areas where off-grid energy can play a critical role. Currently, biomass such as fire wood, charcoal, animal and plant residues are the main sources of energy, unfortunately resulting in environmental degradation. Solar-powered home appliances such as cooking systems, televisions and refrigerator technologies have proven to be effective and environmentally friendly. M-Kopa, an African connected asset financing platform, is exemplary at introducing an innovative solar asset payment model on a pay-as-you-go (PAYG) basis to provide under banked customers in Africa with essential products that includes solar lighting, televisions, fridges, smartphones and financial services.

M-Kopa IV Solar Home System

M-Kopa IV Solar Home System

Ethiopia’s late-comer status allows it to learn from the mistakes of its predecessors while still benefiting from their innovations. To curb some of the problems slowing down its initiative, India has already began reconsidering its import tariff costs, currently at 40% for modules and 25% for solar cells, deprioritizing its domestic manufacturing goals in exchange for more timely results. The State Bank of India (SBI) has also partnered with Tata Power Systems to launch a centralized digital loan application platform, with customer service agents, to ease the process of solar financing for private solar providers. Finally, India is in process to issue a USD 3.3. Billion green bond, to ease the industry’s financing constraints. Ethiopia’s private sector is already making similar progress in the solar pump product line: Hello Solar has partnered with Shell Foundation to help it finance the high capital expenditure its PAYG business model requires and is exploring ways that remittances could be used to help rural residents afford the products.

At a national level, Ethiopia can fund research and design solar pump schemes with drip irrigation at the core of the implementation, minimizing the risk of water scarcity. It should also assess the trade-off between maintaining its protectionist policies versus capitalizing on the vast economic opportunity costs associated with delayed electrification. Because access to electricity is a key macro-catalyst for development, the increased productivity it can enable will translate into higher discretionary income for farmers, amplifying their consumption potential in sectors such as healthcare, education, and banking. Opening the sector to foreign players will allow Ethiopia to strengthen multiple sectors simultaneously and increase the likelihood of reaching its electrification goals on time.

Policymakers and consultants also have a role to play in developing the industry. Some fruitful projects these agents could undertake include:

- Charting the country ground-water map to assess capacity and avoid over-utilization

- Outlining drip irrigation projects, including collaborations between central government, state policy makers and stakeholders to curate necessary implementation schemes

- Designing sustainable financing schemes by engaging with relevant federal and regional governments, development banks, micro-finance institutions and private providers

- Streamlining private entity due-diligence process for non-governmental donors to finance capital intensive business models such as those like “Pay as you Go”

- Assessing and incentivizing local talent and fintech entities towards digitization of the industry – including loan provisions, payment, customer management, distribution, and due-diligence efforts

- Thorough customer usage and experience analysis to provide insights into potential unmet needs

- An in-depth economic analysis of the impact of renewable energy schemes and an evaluation of the multi-sectorial opportunity costs that result from lack of timely implementation

With ambitious power generation targets and tremendous benefits Ethiopia stands to gain once it achieves its goals, major projects like GERD paint only half the picture of the country’s potential. A concerted effort from multiple stakeholders to prioritize off-grid electricity for productive use can unlock many economic opportunities for the nation.